당신은 주제를 찾고 있습니까 “how many years is 67 months – How to Convert years into Months | Years into Months“? 다음 카테고리의 웹사이트 https://ppa.pilgrimjournalist.com 에서 귀하의 모든 질문에 답변해 드립니다: https://ppa.pilgrimjournalist.com/blog/. 바로 아래에서 답을 찾을 수 있습니다. 작성자 Sowmi’s Channel 이(가) 작성한 기사에는 조회수 11,341회 및 좋아요 224개 개의 좋아요가 있습니다.

Table of Contents

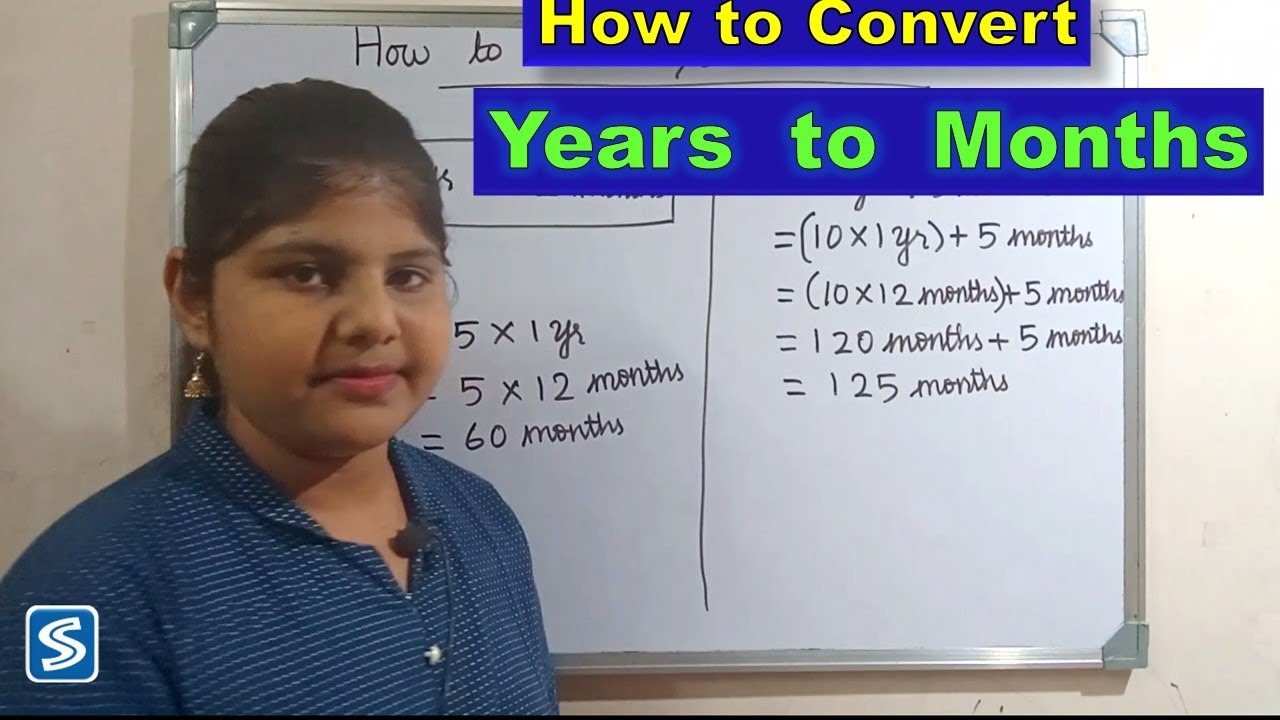

how many years is 67 months 주제에 대한 동영상 보기

여기에서 이 주제에 대한 비디오를 시청하십시오. 주의 깊게 살펴보고 읽고 있는 내용에 대한 피드백을 제공하세요!

d여기에서 How to Convert years into Months | Years into Months – how many years is 67 months 주제에 대한 세부정보를 참조하세요

This video shows how to convert years to months.

Music: https://www.bensound.com

how many years is 67 months 주제에 대한 자세한 내용은 여기를 참조하세요.

67 months to years – Unit Converter

This conversion of 67 months to years has been calculated by multiplying 67 months by 0.0833 and the result is 5.5875 years.

Source: unitconverter.io

Date Published: 3/19/2021

View: 2346

67 Months to Years | 24hourtime.net

Thus, 67 months in years = 5.5833333333 yr (decimal). The non-decimal conversion to years and months is located below the …

Source: 24hourtime.net

Date Published: 5/12/2021

View: 9467

Convert 67 Months to Years – CalculateMe.com

How long is 67 months? What is 67 months in years? 67 mo to y conversion. … A month is 1/12th of a year. In the Gregorian calendar, an average month has exactly …

Source: www.calculateme.com

Date Published: 2/16/2022

View: 3693

How Many Years in 67 Months | Convert – Calculat.IO

Answer: 67 Months It Is 5.58 Years · 5.58 Years · or · 66.942 Months · or · 291.143 Weeks · or · 2,038 Days · or …

Source: calculat.io

Date Published: 5/24/2021

View: 5292

67 mo to yr – How long is 67 months in years? [CONVERT]

67 months is equivalent to 5.58333333333333 years. Conversion formula. How to convert 67 months to years?

Source: converter.ninja

Date Published: 12/23/2022

View: 9924

Convert 67 months to years – Time Calculator

67 months is equal to 5.58 years. … convert 67 months into Nanoseconds, Microseconds, Milliseconds, Seconds, Minutes, Hours, Days, Weeks, Years, etc…

Source: unitconverter.fyi

Date Published: 6/15/2022

View: 2527

67 Months to Years | 67 mon to Y – ConvertWizard.com

Convert 67 Months to Years (mon to Y) with our conversion calculator and conversion tables. To convert 67 mon to Y use direct conversion formula below.

Source: convertwizard.com

Date Published: 5/8/2022

View: 8965

What is 67 Months in Years? Convert 67 mo to yr

The conversion factor from Months to Years is 0.083388698630137. To find out how many Months in Years, multiply by the conversion factor or use the Time …

Source: whatisconvert.com

Date Published: 2/6/2021

View: 3505

67 Months to Years | 67 mo to yr – Convertilo

67 Months is equal to 5.587 Years. Therefore, if you want to calculate how many Years are in 67 Months you can do so by using the conversion formula above.

Source: convertilo.com

Date Published: 6/23/2021

View: 4023

67 Months to Years | Convert 67 mo in yr – UnitChefs

67 Months (mo) to Years (yr). We prove the most accurate information about how to convert Months in Years. Try Our Converter Now!

Source: unitchefs.com

Date Published: 1/18/2021

View: 7254

주제와 관련된 이미지 how many years is 67 months

주제와 관련된 더 많은 사진을 참조하십시오 How to Convert years into Months | Years into Months. 댓글에서 더 많은 관련 이미지를 보거나 필요한 경우 더 많은 관련 기사를 볼 수 있습니다.

주제에 대한 기사 평가 how many years is 67 months

- Author: Sowmi’s Channel

- Views: 조회수 11,341회

- Likes: 좋아요 224개

- Date Published: 2021. 2. 23.

- Video Url link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twiFmXRnU3g

Is 5 years equal to 60 months?

There are 60 months in 5 years. It is a well-known fact that there are 12 months in a year.

How old is 60 months old?

48 Months (4 years) to 60 Months (5 years) – All About Young Children: Information for Families on Children’s Early Development.

How many years is a 60 month term?

Monthly Payments

The biggest advantage of 60-month car loans is that you have five years to pay them off. Because of this, your monthly payments will be much lower than if you have a three or four year loan.

What is 9 months in a year?

| month | short form | |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | June | Jun. |

| 7 | July | Jul. |

| 8 | August | Aug. |

| 9 | September | Sep. |

What is 11 years in dog years?

| Dog Age | Human Age |

|---|---|

| 11 | 65 |

| 12 | 69 |

| 13 | 74 |

| 14 | 78 |

How much is 84 months?

How long is 84 months? 72 months is six years. 84 months is seven years.

How old is 36 months old?

Wow, your child is 3! Three-year-olds want to know how everything works and aren’t afraid to ask questions.

How old is 18 to 36 months in years?

18 Months to 36 Months (3 years) – All About Young Children: Information for Families on Children’s Early Development.

How many months is a 2 year old?

Doctors use certain milestones to tell if a toddler is developing as expected. There’s a wide range of what’s considered normal, so some children gain skills earlier or later than others. Toddlers who were born prematurely reach milestones later.

Is 7 years too long for a car loan?

A seven-year car loan means lower monthly payments than a three- or five-year loan. That sounded good to Hart. And she’s not alone. A third of all new car loans now have terms longer than six years, according to the credit reporting company Experian.

Is it worth it to pay car loan off early?

Paying off a car loan early can save you money — provided there aren’t added fees and you don’t have other debt. Even a few extra payments can go a long way to reducing your costs. Keep your financial situation, monthly goals and the cost of the debt in mind and do your research to determine the best strategy for you.

Is it smart to do a 72 month car loan?

Because of the high interest rates and risk of going upside down, most experts agree that a 72-month loan isn’t an ideal choice. Experts recommend that borrowers take out a shorter loan. And for an optimal interest rate, a loan term fewer than 60 months is a better way to go. You can learn more about car loans here.

Why is June called June?

June, sixth month of the Gregorian calendar. It was named after Juno, the Roman goddess of childbirth and fertility.

What is after May?

June comes after May. It comes before July. July is the seventh month of the year. The seventh month of the year is July.

How do you write 11 months in a year?

…

Convert 11 Months to Years.

| mo | y |

|---|---|

| 11.00 | 0.91667 |

| 11.01 | 0.9175 |

| 11.02 | 0.91833 |

| 11.03 | 0.91917 |

Is 60 months good for a car loan?

Answer provided by. Until the past two or three years, 60-month car loans were the most popular among consumers. However, many buyers are pushing out the loan to 72 or 84 months due to super low interest rates. With that said, a 60-month car loan isn’t bad if it fits your budget and financial goals.

How many complete years are in 50 months?

| mo | y |

|---|---|

| 50.00 | 4.1667 |

| 50.01 | 4.1675 |

| 50.02 | 4.1683 |

| 50.03 | 4.1692 |

How many years old is 30 months?

Your Child’s Development: 2.5 Years (30 Months)

How many months are in a year?

A year is divided into 12 months in the modern-day Gregorian calendar.

How many months are in 5 years?

Question:

How many months are in 5 years?

Converting Years to Months:

The need to convert a certain number of years to months is a common occurrence in the real world. Thankfully, doing so can be done using a simple fact relating months and years along with a bit logic and arithmetic.

Answer and Explanation: 1

Become a Study.com member to unlock this answer! Create your account View this answer

48 Months (4 years) to 60 Months (5 years) – All About Young Children: Information for Families on Children’s Early Development

Information on Children Ages 48 months (4 years)

to 60 months (5 years)

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT 48 MONTHS (4 YEARS) TO 60 MONTHS (5 YEARS) How are children learning about feelings and relationships?

Play the video to see examples of how children are learning about feelings and relationships for ages 48 months (4 years) to 60 months (5 years) followed by a group discussion by parents.

https://allaboutyoungchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/SE-48-60.mp3 Play this audio file to hear a narration of the examples of child behavior from this video.

Play this audio file to hear a narration of the examples of child behavior from this video. Download a PDF version of this print resource.

Social-Emotional Development

Introduction

What are my children learning about themselves and their feelings?

She likes to feel “independent” but still likes to spend time with her parents and family.

Your five-year old is enthusiastic about doing things herself. She may refuse your help, even if she is struggling and frustrated.

He has developed a lot of skills and likes to show you what he has recently learned how to do.

They have lots of ways to describe themselves and their skills. “I’m five now! That is older than four!” “I know all the names of the planets!” “I know how to ride a skateboard! I couldn’t do that when I was a baby.”

They can start cleaning up by themselves, sometimes without being asked.

They have developed some ways to help themselves calm down when distressed, but sometimes need the support and comfort of their adults to help remind them of strategies they can use.

They can express and describe feelings such as “sad,” “mad,” “frustrated,” “confused,” and “afraid,” can explain what caused them, and can ask for specific comfort.

They can sometimes predict what feelings will happen in certain situations: “If she hits me, I’ll feel sad and I won’t want to play with her.”

They can also describe the feelings of other children and sometimes identify the reason they feel that way: “Theo is mad because Laurene knocked down his blocks.”

They can offer comfort and show empathy for others sometimes, especially if they weren’t directly involved in the conflict.

What are they learning about other people and relationships?

Friendships are important to children’s success in school and in life.

Their growing ability to communicate and negotiate with their friends allows them to play for longer periods of time and to engage in more complex kinds of play. Together with friends they can imagine that they are on a spaceship that travels to outer space and can work together to construct it out of cardboard boxes.

They can compare their friends with themselves: “Daniel is the fastest runner, but I can build the highest.”

They may be developing special friendships with certain children and use the words “best friend.”

They are still learning what “friendship” means and may think that if they are mad at someone, they aren’t friends anymore.

They have a variety of skills to enter play with other children. They might watch for a while, start playing beside others, or ask if they can play—for example, suggesting that they could be the “father” in the pretend family play.

They have some negotiation skills and might use them to resolve a conflict with friends. They are more often able to share toys and materials in play with other children, but will still engage in negotiations about “who had it first” and “how long the turn will be.”

They can give directions to others in play—for example, “You have to be the zookeeper, and we will be the animals”—and can sometimes take directions from others. But other times they might get upset and threaten to leave the play if people don’t do what they want.

They can participate in group activities with several other children, and can often wait for a while for their turn to talk.

They like to know what will be happening and if given information about an upcoming transition, may be able to participate cooperatively.

Parents and teachers are very important to them as sources of comfort and information, but they may resist adult direction or try to negotiate, saying, “I’ll clean up my toys if I can watch a video.”

They seem eager to make decisions and continue to do some “testing” to see if the adult is still in charge of a decision.

They are beginning to be able to follow the rules and will remind other children of the rules, even if there isn’t an adult nearby, but sometimes still need to be reminded to follow the rules.

Here are some tips to support your child learning about themselves as a person, learning about other people and learning about their feelings

Learning about self as a person

Include children in real household work like folding laundry, washing the car, taking out the recycling, loading the dishwasher, or feeding the dog. If you rotate the tasks so that he is regularly learning to do something new, he may stay more interested and will also learn different skills.

Take time to talk to her about what she is learning and show interest in her new skills. This lets her know that you are interested in her as a person. Be specific: “You learned how to ride that bike, using your balance. I saw how long you practiced to get it.” This is more helpful to your child than praise like “Great job,” which doesn’t let her know that you were really observing her.

Now that your child is busier with friends, toys and electronic toys, it is even more important that you plan regular time to spend together with him. He still needs to talk with you, read with you, do your favorite activities together and cuddle with you.

She is full of questions and makes some interesting observations about the world. As well as offering her your opinion about things, it is also important to ask her opinion. (child to dad) “Dad, that person just walked across the street, but the light was red.” (dad to child) “I noticed that too. What do you think about that?” Asking your child her opinion gives her a chance to try out her theories, to put her ideas into words and to practice her reasoning skills.

He is able to discuss some more abstract ideas now. You can talk to him about some of the values that are important in your family, for example, kindness, friendship, listening, cooperation, etc. You can ask him questions about these ideas and tell him stories to illustrate these values. These everyday discussions offer you a chance to teach your child about the values and beliefs of your family and culture and give him a chance to “think out loud” with you about his own growing understanding of things.

In her attempt to be “grown up” she may resist doing what you ask her to. Even when you need to stop her or set a limit, you can let her know you understand her idea. If she refuses to clean up her cars, even after you have given her a warning, you can talk to her in the following ways: “It’s time to put your cars away now.” (positive limit) “I know how much you love to play with them.” (acknowledging her idea) “We need to put them away so they won’t get broken or lost.” (offering information) “Are you ready to put them away now or would you like to play for 5 more minutes?” (choice) “How shall we do it? Shall we put them away by color or kind of car?” (invite her ideas) “I know you love to play with your cars, and they need to be put away now. If you can’t put them away now, I’ll put them up for the rest of the day and we’ll try again tomorrow.” (final limit and follow-through, if needed)

Learning about own feelings

Make time regularly to talk about feelings and ask her about her feelings. “How was your day? What were you happy about? Did you get mad about anything? Was there anything sad that happened? What was your favorite part of the day?” “How do you think your friend was feeling today when Derek wouldn’t play with him?” When she shares her feelings and experiences with you, you can listen to her ideas and talk to her about them.

Help her to understand his feelings by offering names for them when she doesn’t have words for them. “It looks like you are feeling sad.” “It can be frustrating when you try to build a tower and it keeps falling down.” “I can see how excited you are to go to your friend’s house.”

Help her to find safe ways to express her feelings. “It looks like you are angry with your friend. Can you tell her what you are angry about?” “It’s not safe to hit someone when you are mad. What else could you do when you are mad that will be safe for you and those around you?”

When your child is fearful, stay close and offer comfort. Sometimes your child doesn’t want to be taken away from the scary situation, but wants you to be there to help. If she is afraid of monsters, you can ask her about what she is worried about. She might want to draw pictures of the monsters she is afraid of. You could even help her make her pictures into a book (stapling it together and writing her words for the story). You can ask her what might make him feel safer. Discussing the things that she is afraid of can help her gain a sense of mastery and knowledge and can help the fear feel more manageable.

Let her know that all her feelings are healthy and that you will listen to or acknowledge her feelings. This allows her to trust you with her feelings and not feel like she has to hide her feelings from you, and sets the stage for her to be able to share her feelings with you for a long time to come.

Learning about other people

Provide opportunities for him to play with other children (at the park, with neighbors or family, in childcare or in community activities).

Check in periodically when he is playing with other children. He may need some help in negotiating, listening to her friends’ ideas, voicing his own ideas and feelings and coming up with solutions when there are conflicts. He may also need some help with safety, as he and his friends might be excited about trying new things and don’t always know how to make safe decisions.

LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT & LITERACY 48 MONTHS (4 YEARS) TO 60 MONTHS (5 YEARS) How are children learning language?

Play the video to see examples of how children are learning language for ages 48 months (4 years) to 60 months (5 years) followed by a group discussion by parents.

https://allaboutyoungchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/LL-48-60.mp3 Play this audio file to hear a narration of the examples of child behavior from this video.

Play this audio file to hear a narration of the examples of child behavior from this video. Download a PDF version of this print resource.

Language Development & Literacy

Introduction

How do children learn language and begin to understand reading and writing?

Around 5 years old, children are able to communicate their ideas and feelings, ask and answer questions, and understand what is said to them. They are able to talk in some detail about things that happened in the past and that will happen in the future.

They can participate in extended conversations with others, responding appropriately and staying on topic most of the time.

They can tell stories and relate sequences of events. They are usually able to distinguish between imaginary and real events in their stories.

At around 5 years old, children like to play with the sounds of words, making up silly rhymes. They also like to make up “nonsense” words and sometimes experiment with “potty” language.

At around 5 years old, many children can recognize letters and are beginning to copy or write them. Many learn to write their names and begin to recognize some favorite words. They are interested in drawing and writing, and many can copy words if you write them first.

Around 5 years old, children also pretend to read books, may recognize specific words and may memorize the story as well as familiar songs.

Bilingual Language Development

How do children in bilingual or non-English-speaking families learn language?

Young children are very skilled at learning language and have the ability to learn two or more languages even before they begin school.

Families who speak a language other than English at home can use their home language as their primary language with children. Learning their home language helps children feel connected to their family and culture. They can learn English at the same time if the family is bilingual or they can learn English when they begin childcare or school.

Families support language learning by talking, reading and singing to their children in their home language. In this way children learn many words and language skills that will help them when they begin learning English.

Check with your local library for books in your home language.

Children who have this opportunity to become bilingual at an early age will benefit from the use of both languages throughout their lives.

Listening and Speaking

How do speaking and listening help a child learn language?

Using language and engaging in conversation are very important first steps to learning to read and to school success. The more words children hear and the bigger their vocabularies, the better they do in school. Children are eager learners of language and are fascinated with the power of language

to communicate their needs, feelings and ideas,

to share their personal experience with others,

to make things happen,

to get and give information,

to solve problems and explore ideas,

to help them make connections with people,

to create and tell their stories,

to make plans for things they want to do, and

to persuade others or argue their point.

Children learn language by listening, talking, practicing new words, and being listened to and responded to. Children learn more words when you use new words with them. Families have many, many everyday opportunities to help children learn language.

Tips for what families can do to support children learning language:

You can support children’s language development during your routine daily activities. Language isn’t something that has to be taught in “special lessons.” When families talk with children they are naturally teaching language. Using language with children is all that families have to do. The more language families use with children, the more children will learn.

In the car, at the store, on a walk, at home doing chores, while child is playing, during meals, or at bedtime When you talk about things that are immediate and familiar, children can understand the language better because they have visual clues and experiences to match your words.

Talk about what you are seeing, what they are doing, what you are doing, what you did together earlier, or what you are going to do later.

Add a few new descriptive words when you are talking to children. One of the ways we naturally build vocabulary with children is by introducing new words along with the familiar ones they already know and with visual clues so they can more easily understand the new words. “There is a dog.” “There is a big, bouncy dog.” “There is a big, bouncy, curly-haired dog who is sniffing the rock and wagging its tail.”

Share stories with them. Stories give you a chance to share what is important to you, what you value and how you think about things. Stories can help children feel connected to you and invested in learning language. Children love to hear stories from your childhood. These stories can teach them about history, family and culture. Stories can be about your day, or about things you are interested in. You can use stories to remember and reflect on your child’s day. Stories don’t have to be long. They can include what happened, how you or your child felt about it, how people solved problems, or what it was like for you to be a child. You can use stories to demonstrate ideas that you value, for example, persistence, creativity, compassion, generosity, caring, bravery, teamwork.

Ask children questions. Asking children questions gives them a chance to reflect on and think about what they know and also offers them an opportunity to practice choosing and articulating words. It also lets them know that you value their ideas.

Ask them about what they see, what they are doing, what they are thinking about, how they feel, what they like, what happened earlier, or what they think is going to happen.

Ask them follow-up questions. When they tell you something, you can ask for more details. Asking more questions challenges them to think more deeply about what they know and to find words to describe it. Responding to your questions is one way for them to stretch their language muscle. “Wow, you and Rigo played dragons. What did the dragons do? Tell me more about the dragons. How do you think dragons make that fire that comes out of their mouths?” “You drew a spaceship? What does your spaceship have inside? What makes your spaceship fly? Where is your spaceship going? Tell me more about your spaceship.”

Ask questions that allow children to create their own answer (avoid questions that have yes or no answers). When we ask children questions that don’t have a “right answer,” they can be more creative and thoughtful in their answer, rather than just trying to figure out what you want them to say.

Here are some examples of questions that might lead to less conversation or more conversation: “What was the funnest thing you did today?” (open-ended—more conversation) “Did you have fun at school today?” (yes/no or closed-ended question—less conversation) “What can you tell me about your friend Theo?” (open-ended—more conversation) “Do you like Theo?” (yes/no or closed-ended question—less conversation)

Ask questions that you don’t have the answer for already. Asking questions that you don’t have the answer for already communicates to children that you are genuinely interested in their thinking and therefore that their thinking is important. “What do you notice on this page?” (unknown answer—a good way to support children’s thinking) “What do you think the dog is going to do?” (unknown answer—a good way to support children’s thinking) “What color is the dog?” (known answer—less supportive of children’s thinking)

You can invite your child to answer the question they asked you. Children usually have a guess already when they ask you a question. Asking children what they think encourages them to put their thoughts into words and gives them more opportunity to participate in conversation with you. “That’s an interesting question. How do you think stars get up in the sky?”

Listen to children. Children will talk more when they know that you are listening. More talking gives them more practice with language.

You can let them know you are listening by making eye contact, allowing quiet space for them to talk or finish what they are saying, turning the TV off, creating “talking time” regularly (for example, sitting on the couch together, taking a walk together, snuggling at bedtime), repeating or restating what they said to let them know you heard them, asking questions, or thanking them for sharing their ideas or stories with you.

You can use technology to support children’s language development Use your phone to record children’s words and stories. When you play it back you can talk about what they said. Use your phone to take photos of things you have seen and done during the day. When you look at the photos with your child you can talk about your observations and activities.

Reading

How do children learn to read?

When you read with children you begin to open up whole new worlds for them. Reading allows them to learn about a powerful form of communication and gives them access to all kinds of information.

Most children love to share a book with a family member. Reading to your child is one of the most important things you can do to help them learn to read and to be successful in school.

Reading doesn’t just happen with books. Children are fascinated with signs, labels, instructions, notes, letters, and emails. Learning the many uses there are for reading helps children be even more excited about learning to read. Early reading experiences for children start with children learning to recognize photos and pictures. They learn that photos and pictures can be named and talked about. They also learn that stories can be told about pictures in books. And eventually they learn that the letters on the page tell the story about the pictures or describe them. For example, they start to understand that there is a connection between the picture of an apple and the letters “a-p-p-l-e” on a page—that the letters represent the idea of an apple.

When children are becoming familiar with books, they are learning many things: that books are important (because they are important to you!) and because they have so much interesting information in them; how you use a book—hold it, turn the pages, talk about every page; how you can use it with someone or by yourself; where the story is (is it in the pictures or in the letters at the bottom of the page or in the memory of the person reading it?); and how books are organized (the title and authors’ names are on the front and the story is inside).

Tips for what families can do to support children in pre-reading activities:

Look at photos and pictures with children, ask them what they see, and talk about what you see. This helps children develop their observation skills and gives them the opportunity to practice and increase their vocabulary. Talking about pictures can help children experience the feeling of reading.

Ask them what they think is happening in the picture. This gives children a chance to practice “telling their own story” and may help them to think of themselves as storytellers and writers.

Notice words in the environment and point them out to children. When we point out the places that words are used in the world, children begin to see the importance of the written word and feel even more motivated to learn how to read those words. When you are in the car, you can talk to children about the road signs. In the grocery store, children can help you “read” the labels on the cans and packages.

Read them what you are writing. When children see writing in process and hear what it means, they can more clearly see the connection between writing letters and communicating a message. “I’m making a list for the grocery store. Here it says ‘cheese,’ and here it says ‘rice.’ What kind of fruit should we put on our shopping list?” “I’m writing a note to your teacher that says we are going out of town next week.”

Read notes and letters out loud to them. “Here is a note your teacher wrote. It says, ‘Dear Families. . .’“

Point to the words you are reading. Pointing to words helps children understand how the spoken word is connected to the written word. “This is a note from Grandma. Here she says, ‘“I love you.’” Here she says, ‘“I’m going to come to visit you.’”“

Read them emails and text messages also. Sometimes words on a screen aren’t as obvious to children. Showing them these words helps them see how technology can also carry written words and communication. Many of the words in their environment are electronic and this can also provide opportunities for learning to read.

Look for opportunities to write down their words. Writing down children’s words is one of the most important things you can do to demonstrate to them the power of writing and reading. If their own words can be “saved” and shared with more people and at a different time, they can feel the power of writing and reading. If they are feeling sad to say good-bye to their friend, you can suggest that they might want to write a note. They can draw the picture and tell you what to write. Once you have written their words down, read them back to your child. If their friend is having a birthday, they can help make a card—by drawing and telling you the words to write. If they build something and want to save it, you can help them make a sign (using their words) to tape on their structure.

Make drawing materials available to them (pencils, pens, markers, chalk). When they draw, you can ask if they want to tell you about it. You can write down their “story” on a post-it note and then ask if they want you to read it back to them. Drawing materials give them a chance to practice how to make lines and shapes—the skills they will eventually need for writing. Even drawing pictures gives them the sense of being able to communicate their ideas in different ways and they can begin to have the experience of being an “author” themselves.

Read books to children. Reading books to children not only gives them practice with all the skills necessary for reading, but it also communicates to them how important reading is to you. Provide a variety of children’s books on a shelf or in a basket that children can reach. You can make regular trips to the library or bookstore to get books for your child. Include reading as a regular activity with your child (find a time every day when you can read books with your child). Turn off the TV to make time for reading. Read books more than once to your child. Children generally love to read the same book many times. Talk about the book with your child. Before turning the page, ask your child what they think is going to happen next. As well as reading the words, you can discuss the story and pictures with your child: “What do you see on this page?”; “Why do you think the boy climbed to the top of that tree?”; “What would you do if you were riding that horse?” Before reading one of your child’s favorite books to him, ask if they want to tell you the story first. Sometimes, when reading to your child, you can point to the words as you read them. Explain to your child what the words on the cover of the book are. “This is the title of the book. It gives you an idea of what the book is about.” “This is the author’s name. The author is the person who wrote the book. This is the illustrator’s name. He is the person who made the pictures for the book.” Talk to your child about letters and sounds. Point out the letters in special words, like your child’s name. “Your name starts with an ‘“S,’” Sergio. Can you think of any other words that have that ‘“ssss’” sound? We can also look around for words that start with ‘“S.’” We could make a list of all the words we hear the ‘“ssss’” sound in.” Play with sounds and rhyming. Using songs, poems or other rhyming words, you can help children hear and compare the sounds of the words. You can play rhyming games in the car. “The bear has black hair. Can you think of a word that sounds like ‘bear’ and ‘hair’?”

Writing

How do children learn to write?

By 5 years old, children may be writing some letters. They might be big and take up the whole page, they might be backward and upside down, but these are the beginning stages of actually writing words.

Many children are interested in learning how to write their names and sometimes want to write the names of their friends as well. Children are most motivated to write about things that are important to them and may be more interested in having you write the word “triceratops” for them to copy than a simpler word.

Children become interested in writing at different ages—some as early as 3, and others at 6. You don’t have to “force” your child to write. If you keep opportunities open and pens, pencils and paper available, most children will initiate writing when they are ready.

When children begin to write, they don’t have to spell things correctly at first. Many children begin to put letters together based on their sounds as they begin to “write.” It is more important that children have the opportunity to practice using the letters than it is that they have all the words spelled correctly.

Tips for what families can do to support children learning to write:

Have a variety of writing tools and paper (pencils, pens, fine-tip markers, paper of different sizes) where children can see them and reach them themselves. Children often have the need to draw pictures or make signs in their play. Having materials readily available will encourage them to use these in their play more often.

You can also include tape and paper strips, so children can make signs or envelopes and can write letters or notes. Some children may like to have paper with wide lines for writing.

Create a favorite “word pouch” for your child that can hold words your child has asked you to write for them. When children can revisit those words, they start to become familiar with what they look like and can begin to start “reading” them.

You can print or buy an alphabet chart so that you and your child can refer to it when she is wanting to know how something is spelled. Posting an alphabet allows your child to reference the letters on their own and may help them to feel like they can begin to write independently.

You can offer sets of letters to your child. Having letters around helps your child become familiar with their shapes and allows her to start arranging them, even before he is fully able to write them. There are different kinds of letters you can buy, including magnetic letters that children can use on the refrigerator, or you can simply write letters on little pieces of thick paper and offer them to children to use in making words.

Invite your child to write with you when you are writing notes or making lists. Children love to be helpful and to participate in adult work. This can spark their interest in learning more about writing. “I’m going to make a shopping list. Do you want to help me?” If you know your child can write certain letters, you can invite him to write them on your list. “I’m writing ‘apples’ on the list and that starts with an ‘A’ like your name. Do you want to write the ‘A’ for me?”

Offer to write children’s stories or words for them. If there is a friend or someone they would like to communicate with, you can offer to help them write a note. If they draw a picture, you can ask them if they want to tell you about it and have you write down their ideas.

NUMBER SENSE 48 MONTHS (4 YEARS) TO 60 MONTHS (5 YEARS) How are children learning about numbers?

Play the video to see examples of how children are learning about numbers for ages 48 months (4 years) to 60 months (5 years) followed by a group discussion by parents.

https://allaboutyoungchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/NS-48-60.mp3 Play this audio file to hear a narration of the examples of child behavior from this video.

Play this audio file to hear a narration of the examples of child behavior from this video. Download a PDF version of this print resource.

Number Sense

Introduction

What are preschool children learning about numbers?

Young children begin to practice the skills needed for arithmetic and math far before they enter elementary school. Most of these skills are developed through their self-initiated play with materials and through simple interactions with adults.

Young children learn counting skills through everyday interactions such as putting plates on the table, counting their fingers to tell you how old they are, and counting the number of apples needed so each child can have one.

Children usually learn how to say “1-2-3-4-5” (sometimes putting the numbers in different order) before they know that each number represents something. For example, they might have three strawberries and count them “1-2-3-4-5,” because they don’t know that each strawberry gets only one number. As a child begins to get this concept, you might see her lining up all the animals and giving each one a leaf to eat. Eventually, they learn that if you are counting something each object gets one number.

Young children are also beginning to understand the ideas of “more” and “less” and will notice if someone has more cookies than they do, but they don’t clearly understand quantity. If they have one cookie and their friend has one cookie cut into two pieces, they might think that their friend has more cookies. Their ideas about “more” and “less” help them learn to compare more than two things. As they get more experience, they will be able to sort three sticks from shortest to longest or three balls from smallest to biggest.

Children around the age of 5 can count to twenty, but may miss some numbers (for example, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-13-14-16-17-19-20). They may count while they are hopping, or waiting for a turn, or just showing you, “I can count to 20!”

They recognize some written numbers: “See the numbers are in the corner of the page. That is a 6. That is a 7.”

Five-year-olds can look at a group of things—up to 4—and tell you the number without counting. In reading a book, they can look at the page and tell you, “Now there are 4 ducks.” During snack, a child can look at her plate and announce, “I have 4 crackers on my plate.”

At five years of age, children can usually count up to 10 objects, pointing at each when they say the number. Putting 10 potatoes in the bag at the grocery store, she can count each one as they go in the bag.

When counting, children at this age can tell you how many things they have, because they understand that the last number they used in counting is the total number they have. “One, two, three, four, five, six. I have six pinecones!” They can also count the number of people in the family and count the number of napkins they need so everyone can have one.

They can also tell you that if more dolls are added to the doll bed, there will be more. Similarly, if they count the number of sticks they have as 8 and the number their friend has as 6, they will tell you that they have more than their friend has or that their friend has fewer than they do. If they have five blocks and their friend has five, they will tell you that they both have the same.

Five-year-old children can do simple addition and subtraction. If they have 6 strawberries, they can ask for one more and tell you they have 7. If they have 5 crackers and they eat two, they might announce, “Now I have three. If I eat two more, I’ll only have one left!” Sometimes they may need to re-count the new group to confirm how many are there.

They can think about two small groups making a larger group when put together. “I have 3 boats and you have 3 boats. If we put them all in the water, there will be 6 boats.” They can also imagine that a bigger group will be smaller if separated into two groups. “There are 4 cookies. That means 2 for you and 2 for me.”

Tips for families to help children in understanding numbers:

Many of the things that families do naturally with children help them to develop their math and number skills. There are many opportunities in our everyday lives where adults are counting things and children are practicing numbers in their play. Here are some suggestions of things families can do:

Count out loud, so your children can hear the sequence of numbers and notice how often you use counting in your day. Count the kisses you give your child, count the trees outside your home, or count the number of times the dog barks.

Point to things as you count them so that children can see how each number you say represents one object.

Shopping, cooking and eating provide many opportunities for counting: “Shall we get 4 apples or 5? Can you count them for me as I put them in the bag?” “If we get 3 yellow apples and 3 red ones, how many will we have? Let’s count them.” “I think I’ll get the bigger bag of tortillas, because we have all our cousins coming for dinner. Can you reach the bigger one for me?” “We have 3 bags of groceries. Do you think they will all fit in our car?” “How many bags would you like to carry in and how many shall I carry?” “After we wash our hands, can you get 5 tortillas out of the bag for me?” “I need to have 4 potatoes washed. Can you get them out of the refrigerator and scrub them in the sink?” “Can you get the plates to put on the table? How many people do we have in our family? How many plates will you need? Can you make sure there are enough chairs for everyone, too?”

Ask your child to guess or predict how many things there are and then count them together. Making predictions, even if children’s guesses are wrong, gives them a chance to think about numbers and increases their interest in counting. “How many buses will come by before our bus gets here?” “How many strawberries do you think are in this basket?”

You can ask your child simple adding or subtracting questions. “If you have five cookies and you eat two, how many will you have left?” “If you have four pennies and I give you one more, how many will you have?” These little games can be done with actual objects so that your child can see the things. Once they are confident with these problems using objects, you can try asking the questions without the objects.

You can also invite your child to ask you number questions.

Children will make lots of mistakes when they are learning about numbers. Without saying that they are “wrong,” you can gently suggest that we count again together. Or you can say, “You counted five ducks and I only see four.”

These conversations about numbers should be fun. If your child seems stressed or doesn’t want to do these games, you can wait and try again later or try a different game. Most young children are naturally interested in numbers. Keeping number activities fun strengthens their natural interest and encourages them to learn more about numbers.

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT 48 MONTHS (4 YEARS) TO 60 MONTHS (5 YEARS) How are children becoming skillful at moving their bodies?

Play the video to see examples of how children are becoming skillful at moving their bodies for ages 48 months (4 years) to 60 months (5 years) followed by a group discussion by parents.

https://allaboutyoungchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/PD-48-60.mp3 Play this audio file to hear a narration of the examples of child behavior from this video.

Play this audio file to hear a narration of the examples of child behavior from this video. Download a PDF version of this print resource.

Physical Development

Introduction

Some of the things you might see with five-year-old children:

Showing a developed sense of balance.

Maintaining balance while standing on one foot for several seconds.

Maintaining balance when they come to a stop after running.

Balancing a bean bag on top of their head.

Walking forward and backward, “balancing” on a wide line pattern on the rug.

Walking along a zigzag pattern on the rug.

Walking down steps using alternating feet without holding railing.

Balancing while walking on the edge of the sandbox.

Playing a game of “freeze”—moving in different ways and stopping, holding the last position for a few seconds.

Balancing a bean bag on the head or different parts of the body while walking along a straight line.

Running and stopping with control at a desired spot.

Running lightly on toes.

Running, sometimes moving around obstacles without falling.

Jumping over a block using both feet.

Jumping forward 3 feet, using both feet together.

Galloping (running, leading with one foot) in a rhythmic way.

Hopping on one foot for several feet and changing direction to land on different targets.

Tips for families to support preschooler physical development:

Preschoolers need lots of opportunities to move, to run, to climb, to jump, to build and to throw. They enjoy carrying heavy things and building with blocks and other natural materials.

Preschoolers love to transport things. They like to carry things and to push things in carts, boxes or trucks. They also enjoy carrying things, such as baskets or purses with handles that they can use to fill and carry— recycled water bottles, or other things they find.

Preschoolers love to build, stacking things as high as they can and creating houses, roads, buildings, zoos, stores, bridges and other structures they can use for pretend play. They will do this with almost anything they can find—cans and boxes from the cupboard, sticks and leaves from outside, small scraps of wood from the lumber store, several large cardboard boxes, or sets of building blocks or snap together blocks.

Preschoolers also love to climb and some will climb on anything they can find (chairs, tables, shelves, couches, benches). Decide what is safe for your child to climb on and remind them to climb there when they start climbing on other things. You can also use mattresses, cushions and low platforms for children to climb on and use in building forts. Outdoor playgrounds provide opportunities for climbing for children, as do natural areas with logs, boulders and hills. You and your child can explore your neighborhood for appropriate climbing places. Children will sometimes fall when they are climbing, and most of the time they catch themselves and only get small scratches. These simple falls are also how they learn. They often want to go back to the same spot to try climbing again and will do it successfully because of what they learned the previous time. When your child begins to climb, it is important that you look around the area to see if it is a safe environment.

Preschoolers enjoy being outside. Even short walks outside give children a chance to try out different surfaces for walking, running, galloping, hopping and jumping, and to watch the seasons and experience what the community has to offer. Children often put a lot of physical energy into their play. Most are naturally motivated to try new physical challenges and practice new skills.

Preschoolers enjoy challenges. If you are walking on the sidewalk, you might want to set different goals for them. “Can you run to the big tree? Can you hop all the way to the corner? Can you hop for 3 steps and walk for 3 steps and hop for 3 again? Shall we try walking backward for a few steps, walking forward a few steps and then walking backward again? Can you walk on the line down the center of the sidewalk? Can you walk on this squiggly crack in the sidewalk?”

Children at this age also enjoy throwing. You can provide a variety of soft balls that they can throw. They may also be interested in beginning to hit balls with things like bats, sticks, or cardboard tubes.

Preschoolers also like to stretch their muscles by carrying or moving heavy things. A sealed bottle or box of laundry detergent would be fun for them to carry inside for you. They enjoy carrying small stools around so they can reach a book off the shelf. They can help bring in the groceries or push the laundry basket to the table for folding. Helping you with “grown-up” work gives children opportunities to develop their physical skills and also to develop their emotional and social skills.

Children around the age of 5 love wheel toys, small tricycles and bikes, wagons, carts and trucks, all of which provide ways for them to use their physical skills and also can be part of their pretend play.

APPROACHES TO LEARNING 48 MONTHS (4 YEARS) TO 60 MONTHS (5 YEARS) What skills help children learn?

Play the video to see examples of what reasoning skills children are learning for ages 48 months (4 years) to 60 months (5 years) followed by a group discussion by parents.

https://allaboutyoungchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/AL-48-60.mp3 Play this audio file to hear a narration of the examples of child behavior from this video.

Play this audio file to hear a narration of the examples of child behavior from this video. Download a PDF version of this print resource.

Approaches to Learning

Introduction

What skills do preschool-aged children use to solve problems?

One skill that preschool children use to solve everyday problems is math reasoning.

Math concepts like number, counting, shape and size all help children with solving problems. Children use these skills to choose what size plate they will need for their quesadilla, to figure out how many cars they need so each of their friends can have one and to search for a blanket big enough to cover two babies.

A young preschool child may begin by trying an idea that doesn’t work. An older preschool child may try several strategies, finally finding one that works. Whether their ideas work at first doesn’t matter as much as the fact that they are practicing using these ideas, testing them out and changing their course of action when necessary. These strategies are useful in everyday problem-solving, as well as in developing other math skills.

Children also use observation and investigation skills to solve problems.

Children use all their senses to gather information, and to construct meaning and knowledge.

They are naturally curious observers and notice small things that many adults miss, like the ants coming out of the crack in the sidewalk.

Children may also use tools provided to them for measuring or observing, with the guidance of adults. For example, when observing a leaf, they may use a magnifying glass to see the “lines” more clearly or use a ruler (or unit blocks) to measure its length. Through observation, children begin to recognize and describe similarities and differences between one object and another.

Children use their developing skill at careful observation to compare and contrast objects and events and classify them based on different attributes. For example, a child might separate all the “pointy” leaves from all the round leaves or separate the big leaves from the small ones.

Children may also investigate objects and events by trying things to see what happens. For instance, they may investigate what happens to the toy car when it rolls down ramps with bumpy or smooth surfaces, test what happens to plants placed in locations with or without light, or test out their ideas of how to use pipes to make water go up and down in the water table.

They learn to make predictions about changes in materials and objects based on their knowledge and experience, and to test their predictions through observations or simple experiments.

Children use their skills of observation and investigation to ask questions, observe and describe observations, use scientific tools, compare and contrast, predict, and make inferences.

Children use expanded mathematical thinking to solve problems every day.

For example:

A child, after setting the table for dinner, might notice that there aren’t enough chairs for everyone and bring an extra stool over.

A child might use one object to measure another. For example, she might lay books end-to-end to measure how long her bed is.

A child might predict how many grapes are in a bunch and then suggest that he and you count them to find out.

A child might be building a road with long blocks and, when she can’t find any more long blocks, might use two smaller blocks to “fill in” for the longer block.

A child, when cutting paper money for his friends to use at his “grocery store,” might announce, “I need to cut two more dollars for Ziya and Dylan.”

A child might sort her animals into two groups, big animals and small animals, and then get big leaves for the big ones to eat and small leaves for the smaller ones to eat.

Children demonstrate curiosity and an increased ability to ask questions about objects and events in their environment.

A child, when playing with cars, might use a board to create a sloped ramp and roll different toy cars down the ramp. She might check which car goes the farthest when rolling down the ramp.

A child, while digging in the mud, might see a worm and wonder, “Does it live in the ground? I see another one. Is it their home?”

A child, while outside, might look up and ask a parent, “How come I can see the moon in the daytime?”

A child, while sorting different rocks, might pick up one of the rocks and wash it with soap and water. Then he might get the magnifying glass to observe it more closely.

Children observe objects and events in the environment and describe them in greater detail.

A child might observe a sweet potato growing in a jar and identify the buds and roots, and might also communicate, “There are white roots going down and small leaves.” The child might take a photograph of the sweet potato, with the teacher’s assistance, to document the potato’s growth.

A child, after a walk on a rainy day, might describe what the raindrops look like and how they feel, sound, smell, and taste.

A child with visual impairments might manipulate seashells on the sand table and describe what she touches: “It’s bumpy and round,” or “It’s smooth and flat.”

A child, observing a snail closely, might describe it: “It is hard like a rock. Its body looks very soft. It moves very, very slowly. It has two long pointy things [antennas] sticking out.”

A child might observe a caterpillar (or a picture of a caterpillar) closely and draw a picture of the caterpillar in his journal. He might then communicate, “It has stripes—yellow, white, and black—like a pattern.”

Children can identify and use a greater variety of observation and measuring tools, such as measuring tapes and scales.

A child might ask for a magnifying glass to observe a worm more closely and communicate, “I need the magnifying glass to look very close.”

A child, fascinated with the growth of her green beans, might get a ruler and say to her parent, “I want to see how big it is.”

A child, while preparing dough, might use a measuring cup to pour one cup of flour.

A child, while building, might stack blocks to his height and count the blocks to measure his height.

Children compare objects and events and describe similarities and differences in greater detail.

A child might observe that the plants she has been watering are “bigger, and the leaves are green, but the one that didn’t get watered has yellow leaves and looks dead.”

A child might explore different kinds of squash by using sight and touch and describe their similarities and differences: “These are more round, but this is long. This squash is yellow and green and is very smooth, but that one feels bumpy.”

A child might compare objects that can roll down a ramp (such as balls, marbles, wheeled toys, or cans) with objects that cannot roll down (such as a shovel, block, or book). For example, he might refer to objects that can roll down and communicate, “These are round and have wheels.”

A child might compare a butterfly with a caterpillar (while observing pictures or actual objects); for example, she might communicate that the butterfly can fly and the caterpillar cannot and that the butterfly has a different shape and different colors.

A child might observe and describe what the sky looks like on a foggy day and how it is different on a sunny day.

A child, when working in the garden, might use a real shovel and describe how it is similar to or different from the toy shovel in the sandbox area.

Children might demonstrate an increased ability to make predictions and check them.

A child, after planting sunflower seeds, might communicate, “The seeds will grow, and there will be sunflowers.” Then, he might observe the plant daily for changes.

A child, in response to the question, “What do you think will happen if water is added to the flour?” might predict, “The flour will feel sticky and will not look like flour anymore. The water and the flour will mix together.”

A child might cut open a tomato, observe what it looks like inside, and comment, “I thought there would be no seeds inside the tomato, but now I see tiny seeds inside.”

A child might bring an object to the bathtub and predict whether it will sink or float. Then she might put the object in water and observe what happens. Then she might comment to her parent, “Yes, I knew it! It is floating.”

Children have increased ability to use observations to draw conclusions.

A child might observe many different fruits and vegetables and communicate that fruits have seeds and vegetables do not.

A child, after observing the toy cars going down the ramp, might conclude that they go down fastest when the ramp is steep.

A child might observe a picture of an unfamiliar animal. Then she might notice the wings and communicate, “It is a bird. I know it, because it has wings.”

A child might observe a picture of a child dressed in a jacket, a scarf, mittens, and a hat and communicate that it must have been very cold outside.

Tips for families in helping children to practice mathematical thinking, to be observant, and to engage in investigation:

Months of the Year

Months of the Year

The table below shows the months of the year used in English-speaking countries and many other parts of the world. The list shows the order of the months, starting from January (month 1).

The abbreviations or short forms shown are the most common, but other abbreviations are possible, for example: Ja./Fe./Ma. or J./F./M.

The days column shows the number of days in the month. All months have 30 or 31 days, except for February which has 28 days (29 in a leap year).

Every fourth year, the month of February has 29 days instead of 28. This year is called a “leap year” and the 29th day of February is a “leap day”. A leap year has 366 days instead of the usual 365. Most years that can be cleanly divided by four are leap years. 2016, 2020 and 2024, for example, are leap years.

month short form days season 1 January Jan. 31 winter 2 February Feb. 28/29 3 March Mar. 31 spring 4 April Apr. 30 5 May May 31 6 June Jun. 30 summer 7 July Jul. 31 8 August Aug. 31 9 September Sep. 30 autumn 10 October Oct. 31 11 November Nov. 30 12 December Dec. 31 winter

The seasons are approximate and depend on latitude. Some parts of the world have only three seasons. The seasons shown here are for the North Temperate Zone (for example North America). In the southern hemisphere, the seasons are reversed.

67 months to years

Months to years – Time Converter – 67 years to months

This conversion of 67 months to years has been calculated by multiplying 67 months by 0.0833 and the result is 5.5875 years.

Convert 67 Months to Years

In the Gregorian calendar, a year has on average 365.2425 days. It is based on the amount of time it takes for the Earth to rotate the sun.

How Many Years in 67 Months

About “Convert date units” Calculator

This online date converter will help you to convert Seconds/Minutes/Hours/Days/Weeks/Months or Years. For example, What is 67 Months in Years? Select what you want to convert (e.g. ‘Years’), quantity (e.g. ’67’) and target units (e.g. ‘Months’). After that, click the ‘Convert’ button.

How long is 67 months in years? [CONVERT] ✔

67 months is equivalent to 5.58333333333333 years. [1]

Conversion formula

How to convert 67 months to years?

We know (by definition) that: 1 mo ≈ 0.083333333 yr

We can set up a proportion to solve for the number of years.

1 mo 67 mo ≈ 0.083333333 yr x yr

Now, we cross multiply to solve for our unknown x :

x yr ≈ 67 mo 1 mo * 0.083333333 yr → x yr ≈ 5.583333311 yr

67 Months to Years

Amount:

From: ACR – Acres CMK – Square centimeters FTK – Square foots HAR – Hectars INK – Square Inches KMK – Square kilometers MIK – Square miles MTK – Square meters YDK – Square yards ANN – Years DAY – Days HUR – Hours MCS – Microseconds MIN – Minutes MLS – Milliseconds MON – Months SEC – Seconds WEE – Weeks BIT – Bits BYT – Bytes EBI – Exabits EBY – Exabytes GBI – Gigabits GBY – Gigabytes KBI – Kilobits KBY – Kilobytes MBI – Megabits MBY – Megabytes PBI – Petabits PBY – Petabytes TBI – Terabits TBY – Terabytes BLL – Barrels (Oil) CMQ – Cubic centimeters FTQ – Cubic foots GLI – Gallons (UK) GLL – Gallons (US liquid) LTR – Liters MLT – Milliliters MTQ – Cubic meters OZI – Ounces UK BTU – BTU CAL – Calories ERG – Erg EVL – Electron Volt FPD – Foot-Pound HPH – Horsepowers-Hour IPD – Inch-Pound JOU – Joules CMT – Centimeter DMT – Decimeters FOT – Foots INH – Inches KMT – Kilometers MMT – Millimeters MTR – Meters SMI – Miles YRD – Yard CTM – Carats GRM – Grams KGM – Kilograms LBR – Pounds MGM – Milligrams ONZ – Ounces TNE – Tons (metric) DEG – Degrees GRD – Grads RAD – Radians FPM – Foots/Minute FPS – Foots/Second KMH – Kilometers/Hour KMS – Kilometers/Second KNT – Knots MPH – Miles/Hour MTS – Meters/Second GCC – Grams/Cubic Centimeter KCC – Kilograms/Cubic Centimeter KLI – Kilograms/Liter KMC – Kilograms/Cubic Meter OCI – Ounces/Cubic Inch OGL – Ounces/Gallon PCF – Pounds/Cubic Foot PCI – Pounds/Cubic Inch PGL – Pounds/Gallon JCM – Joules/Centimeter KGF – Kilogram Force NWN – Newtons PFC – Pound Force A0 – Bohr, atomic unit of length AST – Angstrom AU – Astronomical unit CBL – cable length (imperial) CBL(US) – Cable length US CH – Сhains F – French charriere FM – Fermi FNG – Finger FNG(CLOTH) – Finger (cloth) FTM – Fathom FUR – Furlong HH – Hand LD – Light-day LEA – league (land) LH – Light-hour LM – Light-minute LN – Line LNK (G.S.) – Link (Gunter’s; Surveyor’s) LNK (R.E.) – Link (Ramsden’s; Engineer’s) LS – Light-second LY – Light-year M – Metre (SI base unit) MIL – Mil (Sweden and Norway) MILE DATA – Miles (tactical or data) MK – Mickey NAIL – Nail (cloth) NL – Nautical league NM – Nanometre NMI – Nautical miles NMI I – Nautical mile P – Palm PC – Parsec PICA – Pica PM – Picometre (bicron, stigma) POINT – point (American, English) PT – Pace QUART – Quarter SHAKU – Shaku (Japan) SPT – Spat TH – Mil (thou) TWP – Twip UM – Micrometer (old: micron) XU – X unit; siegbahn ABA – Electromagnetic Unit Abampere AMP – Ampere (Si Base Unit) ESU – Esu Per Second Statampere (Cgs ABC – Abcoulomb Electromagnetic Unit ATU – Atomic Unit Of Charge CLM – Coulomb FRD – Faraday MAH – Milliampere Hour STT – Statcoulomb Franklin Electrost ABV – Abvolt (Cgs Unit) STV – Statvolt (Cgs Unit) VLT – Volt (Si Unit) ACF – Acre-Foots ACI – Acre-Inchs BIB – Barrels (Petroleum) BII – Barrels (Imperial) BIU – Barrels (Us Dry) BKT – Buckets (Imperial) BRO – Gallons (Beer) BUD – Bushels (Us Dry Level) BUI – Bushels (Imperial) BUU – Bushels(Us Dry Heaped) CMB – Coombs CMI – Cubic Miles CP – Cups CRF – Cord-Foots CRW – Cords (Firewood) CUF – Cubic Fathoms CUI – Cubic Inchs CUT – Cubic Foots CUY – Cubic Yards DSI – Dashs (Imperial) DSS – Dessertspoons (Imperial) DSU – Dashs (Us) FBM – Board-Foots FFT – Fifths FID – Fluid Drachms (Imperial) FIS – Fluid Scruples (Imperial) FLB – Barrels (Us Fluid) FLU – Fluid Drams (Us) Us Fluidram FRK – Firkins GAI – Gallons (Imperial) GAU – Gallons (Us Dry) GAW – Gallons (Us Fluid Wine) GLU – Teacups (gills) GTT – Drops HDI – Hogsheads (Imperial) HHU – Hogsheads (Us) JGR – Jiggers (Bartending) KLD – Kilderkins LMD – Lambdas LOD – Loads LST – Lasts M3 – Cubic Metres (Si Unit) MII – Minims (Imperial) MIU – Minims (Us) OZF – Ounces (Fluid Us Food Nutritio PER – Perchs PKI – Pecks (Imperial) PKU – Pecks (Us Dry) PNI – Pinchs (Imperial) PNU – Pinchs (Us) PON – Ponys POT – Pottle Quarterns PP – Butt Pipes PTI – Pints (Imperial) PUD – Pints (Us Dry) PUF – Pints (Us Fluid) QRF – Quart S(Us Fluid) QRT – Quarter Pails QTI – Quarts (Imperial) QTU – Quarts (Us Dry) RGS – Register Tons SCI – Sack (Imperial) Bags SCU – Sacks(Us) SHT – Shots (Us) SM – Seams STK – Strikes (Imperial) STU – Strikes(Us) TBC – Tablespoons (Canadian) TBF – Tablespoons (Us Customary) TBM – Tablespoons (Metric) TBS – Tablespoons (Australian Metric TCA – Teaspoons (Canadian) TFD – Tablespoons (Us Food Nutrition TIM – Teaspoons (Imperial) TMF – Timber Foots TMT – Teaspoons (Metric) TND – Tons (Displacement) TNT – Tons (Water) TNW – Tons (Freight) TSC – Teaspoons (Us Customary) TSF – Teaspoons (Us Food Nutrition L TSI – Tablespoons (Imperial) TUN – Tuns USF – Ounces (Fluid Us Customary) WEY – Wey (Us) ACM – Atmosphere-Cubic Foot Per Minu ACS – Atmosphere-Cubic Foot Per Seco ATC – Atmosphere-Cubic Centimetre Pe ATH – Atmosphere-Cubic Foot Per Hour BTJ – Btu (International Table) Per BTN – Btu (International Table) Per BTS – Btu (International Table) Per CAS – Calorie (International Table) ERS – Erg Per Second FMF – Foot-Pound-Force Per Minute FT – Foot-Pound-Force Per Hour FTO – Foot-Pound-Force Per Second HPS – Horsepower LAM – Litre-Atmosphere Per Minute LSC – Lusec LTS – Litre-Atmosphere Per Second PNC – Poncelet SQL – Square Foot Equivalent Direct TC – Ton Of Air Conditioning TMS – Atmosphere-Cubic Centimetre Pe TRM – Ton Of Refrigeration (Imperial TRR – Ton Of Refrigeration (It) AMU – Atomic Mass Unit Unified AT – Ton Assay (Short) ATS – Ton Assay (Long) BAC – Bag (Coffee) BDM – Bag (Portland Cement) BRG – Barge CLV – Clove CRT – Crith CT – Carat (Metric) DA – Dalton DRT – Dram (Apothecary Troy) DWT – Pennyweight GAM – Gamma GR – Grain GV – Grave KIP – Kip LB – Pound (Metric) LBA – Pound LBT – Pound (Troy) LBV – Pound (Avoirdupois) ME – Atomic Unit Of Mass Electron R MRK – Mark MTE – Mite MTM – Mite (Metric) OZ – Ounce (Us Food Nutrition Label OZT – Ounce (Apothecary Troy) OZZ – Ounce (Avoirdupois) PNN – Point Q – Quintal (Metric) QR – Quarter (Informal) QRI – Quarter (Imperial) QRL – Quarter Long (Informal) SAP – Scruple (Apothecary) SH – Ton Short SLG – Slug Geepound Hyl SLH – Sheet ST – Stone SWT – Hundredweight (centum weight o TON – Ton Long WY – Wey ZTR – Zentner ARE – Ares BD – Boards BHE – Boiler Horsepower Equivalent D BR – Barns BRN – Baronys CDA – Cuerda Pr Surveys CRD – Cords CRI – Circular Inchs CRM – Circular Mils DNM – Dunams GNT – Gunthas HD – Hides RO – Roods SCT – Sections SHD – Sheds SII – Square Link Gunters Internati SLR – Square Link Ramsdens SQC – Square Chains International SQM – Square Mil Square Thous SQR – Square Rod/Pole/Perchs SRR – Square Roofings STR – Stremmas TWN – Townships YLN – Yardlands ARM – Arcminute Moa ARS – Arcsecond CNS – Centesimal Second Of Arc CNT – Centesimal Minute Of Arc DOA – Degree (Of Arc) GRA – Grad Gradian Gon OCT – Octant QRD – Quadrant SGN – Sign SXT – Sextant µ – Angular Mil ATA – Atmosphere (Technical) ATM – Atmosphere (Standard) BAR – Bar BRY – Barye (Cgs Unit) CMH – Centimetre Of Mercury CMW – Centimetre Of Water (4 °C) FTH – Foot Of Mercury (Conventional) FTW – Foot Of Water (392 °F) IMC – Inch Of Mercury (Conventional) INW – Inch Of Water (392 °F) KM – Kilogram-Force Per Square Mill KSI – Kip Per Square Inch LTP – Long Ton Per Square Foot MHG – Micrometre Of Mercury MMH – Millimetre Of Mercury MMW – Millimetre Of Water (398 °C) PA – Pascal (Si Unit) PD – Poundal Per Square Foot PSF – Pound Per Square Foot PSI – Pound Per Square Inch PZ – Pièze (Mts Unit) STP – Short Ton Per Square Foot TOR – Torr ATN – Atomic Unit Of Force DYN – Dyne (Cgs Unit) KFF – Kilogram-Force Kilopond Grave- KI – Kip Kip-Force MGF – Milligrave-Force Gravet-Force OZC – Ounce-Force PDL – Poundal SN – Sthene (Mts Unit) TNF – Long Ton-Force TNL – Short Ton-Force AUC – Atomic Unit Of Time CTN – Century CYC – Callippic Cycle DEC – Decade FN – Fortnight HEL – Helek HIP – Hipparchic Cycle JFF – Jiffy KEH – Ke (Quarter Of An Hour) LSR – Lustre Lustrum MD – Milliday MLL – Millennium MMN – Moment MOF – Month (Full) MOG – Month (Greg Av) MOH – Month (Hollow) MOS – Month (Synodic) MTN – Metonic Cycle Enneadecaeteris OC – Octaeteris PLN – Planck Time SGM – Sigma SHK – Shake STH – Sothic Cycle SVD – Svedberg YR – Year (Common) YRG – Year (Gregorian) YRJ – Year (Julian) YRL – Year (Leap) YRM – Year (Mean Tropical) B39 – British Thermal Unit (39 °F) B59 – British Thermal Unit (59 °F) B60 – British Thermal Unit (60 °F) B63 – British Thermal Unit (63 °F) BOE – Barrel Of Oil Equivalent BRT – British Thermal Unit (Iso) BTI – British Thermal Unit (Internat BTM – British Thermal Unit (Mean) BTT – British Thermal Unit (Thermoch C15 – Calorie (15 °C) C20 – Calorie (20 °C) C98 – Calorie (398 °C) CAM – Calorie (Mean) CFT – Cubic Foot Of Atmosphere Stand CHU – Celsius Heat Unit CL – Calorie (Us Fda) CLTH – Calorie (Thermochemical) CN – Cubic Foot Of Natural Gas CTA – Cubic Centimetre Of Atmosphere CYD – Cubic Yard Of Atmosphere Stand EH – Hartree Atomic Unit Of Energy FTD – Foot-Poundal IMG – Gallon-Atmosphere KCA – Kilocalorie Large Calorie KWH – Kilowatt-Hour Board Of Trade U LTM – Litre-Atmosphere QD – Quad RDB – Therm (Ec) RY – Rydberg TCE – Ton Of Coal Equivalent THR – Therm (Us) THU – Thermie TN – Ton Of Tnt TOE – Tonne Of Oil Equivalent BAN – Ban Hartley BSH – Bit Shannon CD – Candela (Si Base Unit) Candle CPD – Candlepower (New) JK – Si Unit NAT – Nat Nip Nepit NBL – Nibble BQ – Becquerel (Si Unit) CI – Curie RD – Rutherford (H) C – Speed Of Light In Vacuum FPF – Furlong Per Fortnight FPH – Foot Per Hour IPH – Inch Per Hour IPM – Inch Per Minute IPS – Inch Per Second MCH – Mach Number MPM – Mile Per Minute MPS – Mile Per Second MS – Metre Per Second (Si Unit) SPS – Speed Of Sound In Air CDF – Candela Per Square Foot CDI – Candela Per Square Inch CDM – Candela Per Square Metre (Si U FL – Footlambert LMB – Lambert SB – Stilb (Cgs Unit) CEL – Celsius DDE – Degree Delisle DNE – Degree Newton FAN – Fahrenheit GMR – Regulo Gas Mark KEL – Kelvin’s RAN – Rankine REA – Reaumur RME – Degree Rømer CFM – Cubic Foot Per Minute FTS – Cubic Foot Per Second GPD – Gallon (Us Fluid) Per Day GPH – Gallon (Us Fluid) Per Hour GPM – Gallon (Us Fluid) Per Minute INM – Cubic Inch Per Minute INS – Cubic Inch Per Second LPM – Litre Per Minute MQS – Cubic Metre Per Second (Si Uni CM – Coulomb Meter DB – Debye EA0 – Atomic Unit Of Electric Dipole FC – Footcandle Lumen Per Square Fo LMN – Lumen Per Square Inch LX – Lux (Si Unit) PH – Phot (Cgs Unit) FHP – Foot Per Hour Per Second FMS – Foot Per Minute Per Second FP – Foot Per Second Squared G – Standard Gravity GAL – Gal Galileo IP – Inch Per Minute Per Second IP2 – Inch Per Second Squared KNS – Knot Per Second MM – Mile Per Minute Per Second MP – Mile Per Hour Per Second MP2 – Mile Per Second Squared MSA – Metre Per Second Squared (Si U FT2 – Square Foot Per Second M2S – Square Metre Per Second (Si Un STX – Stokes (Cgs Unit) FTP – Foot-Poundal MKG – Metre Kilogram-Force NEM – Newton Metre (Si Unit) GML – Gram Per Millilitre LAB – Pound (Avoirdupois) Per Gallon LBF – Pound (Avoirdupois) Per Cubic LBI – Pound (Avoirdupois) Per Cubic LBL – Pound (Avoirdupois) Per Gallon OFT – Ounce (Avoirdupois) Per Cubic OG – Ounce (Avoirdupois) Per Gallon OGA – Ounce (Avoirdupois) Per Gallon OIN – Ounce (Avoirdupois) Per Cubic SFT – Slug Per Cubic Foot GSS – Gauss (Cgs Unit) TSL – Tesla (Si Unit) GY – Gray (Si Unit) RDD – Rad LBH – Pound Per Foot Hour LBS – Pound Per Foot Second LFT – Pound-Force Second Per Square LIN – Pound-Force Second Per Square PAS – Pascal Second (Si Unit) PSU – Poise (Cgs Unit) MX – Maxwell (Cgs Unit) WB – Weber (Si Unit) REM – Röntgen Equivalent Man SV – Sievert (Si Unit)

What is 67 Months in Years?

Convert 67 Months to Years To calculate 67 Months to the corresponding value in Years, multiply the quantity in Months by 0.083388698630137 (conversion factor). In this case we should multiply 67 Months by 0.083388698630137 to get the equivalent result in Years: 67 Months x 0.083388698630137 = 5.5870428082192 Years 67 Months is equivalent to 5.5870428082192 Years.

How to convert from Months to Years The conversion factor from Months to Years is 0.083388698630137. To find out how many Months in Years, multiply by the conversion factor or use the Time converter above. Sixty-seven Months is equivalent to five point five eight seven Years.

Definition of Month A month (symbol: mo) is a unit of time, used with calendars, which is approximately as long as a natural period related to the motion of the Moon; month and Moon are cognates. The traditional concept arose with the cycle of moon phases; such months (lunations) are synodic months and last approximately 29.53 days. From excavated tally sticks, researchers have deduced that people counted days in relation to the Moon’s phases as early as the Paleolithic age. Synodic months, based on the Moon’s orbital period with respect to the Earth-Sun line, are still the basis of many calendars today, and are used to divide the year.

67 Months to Years – 67 mo to yr

Definition of units

Let’s see how both units in this conversion are defined, in this case Months and Years:

Month (mo)

A month (symbol: mo) is a unit of time, used with calendars, which is approximately as long as a natural period related to the motion of the Moon; month and Moon are cognates. The traditional concept arose with the cycle of moon phases; such months (lunations) are synodic months and last approximately 29.53 days. From excavated tally sticks, researchers have deduced that people counted days in relation to the Moon’s phases as early as the Paleolithic age. Synodic months, based on the Moon’s orbital period with respect to the Earth-Sun line, are still the basis of many calendars today, and are used to divide the year.

Year (yr)

A year (symbol: y; also abbreviated yr.) is the orbital period of the Earth moving in its orbit around the Sun. Due to the Earth’s axial tilt, the course of a year sees the passing of the seasons, marked by changes in weather, the hours of daylight, and, consequently, vegetation and soil fertility. In temperate and subpolar regions around the globe, four seasons are generally recognized: spring, summer, autumn and winter. In tropical and subtropical regions several geographical sectors do not present defined seasons; but in the seasonal tropics, the annual wet and dry seasons are recognized and tracked. A calendar year is an approximation of the number of days of the Earth’s orbital period as counted in a given calendar. The Gregorian, or modern, calendar, presents its calendar year to be either a common year of 365 days or a leap year of 366 days.

67 Months to Years

67 Months =

Years